"The eye sees only what the mind is prepared to comprehend."

Henri Bergson

Rarely does one get the opportunity to recognize and document our own failure or be able to extract valuable lessons from it. It’s a tremendously humbling experience! The following is a case that has forced me to critically revaluate my treatment goals and approach when dealing with TMD patients presenting with bruxism.

What’s your criteria for success?

Pierre was a patient referred to me specifically for a full-mouth occlusal rehabilitation of his severely worn Class 2 division II malocclusion in 1994 when he was working in South East Asia. He had seen several dentists in Paris for TMJ-related problems and been treated with cognitive behavioral therapy, hypnosis, anxiolytic and antidepressant medication, occlusal equilibration and occlusal splints. He had orthodontic treatment with 4 bicuspid extractions as a teenager and a history of bilateral reciprocal TMJ clicking and intermittent locking.

I completed his prosthodontic rehabilitation following orthotic therapy and some pre-restorative orthodontics circa 1995. In retrospect, I dare say the prosthodontics was perfectly executed to American Board standards: his condyles were ‘romanced’ into centric relation, a mutually protected occlusal scheme was coordinated with type A canine guidance, tripodized posterior cuspal morphology with metal occlusals holding shimstock, and quite reasonable facially-generated aesthetics. Both he and I thought I did a good job and he left for home happy. Admittedly, our criteria for clinical success was shamefully mechanistic.

In 2008, he came back to see me when he was reassigned to the Far East. The crowns I made were still looking pristine as he was religious about wearing his full coverage flat plane Michigan splint to sleep. He no longer had TM joint pains but continued to suffer persistent neck pain and occipital headaches, worse on waking. He was still bruxing heavily (inferred from the significant occlusal wear on his splint) and his sleep was progressively fragmented and unrestorative. Any relief from manipulative therapy by his physiotherapist was short-lived (only lasting a maximum of 3 days) as he habitually slept on his stomach and face. Despite his strict diet and commitment to daily exercise and meditation, he constantly complained of fatigue and had an Epworth Daytime Sleepiness score of 14. You see, in 1994 I felt I was only responsible for his bite. Back then I didn’t bother to ask the right questions – it was not my job!

Till today, most dentists confronting patients with severe attrition continue to be more concerned about the hows (i.e. always looking for cookbook recipes or some occlusal rehabilitation philosophy to ‘fix’ the stomatognathic damage) when they should really be asking the whys and whens, and whether or not it could have been prevented in the first place. We need to change this ‘repair, restore and replace’ mentality!

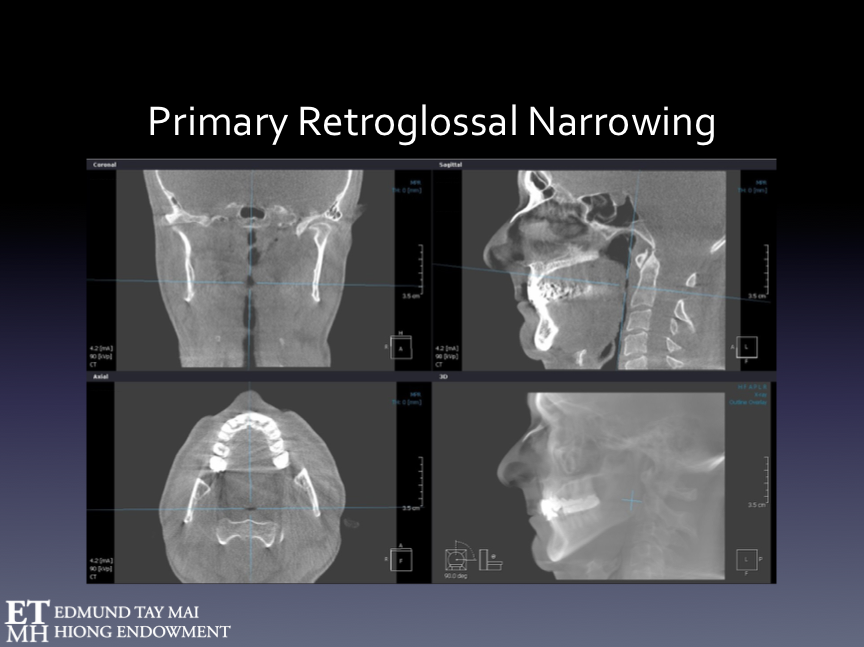

By 2008, I had acquired better imaging capabilities (in the form of a large field Cone Beam CT) and also learned a lot more about sleep disorders especially an entity known as Upper Airway Resistance Syndrome. I could now see and document the extremely narrow retro-glossal dimension of the patient’s upper airway even when he was awake and upright (Fig. 21a), and began to better appreciate why he had never been able to sleep supine. I subsequently fitted him with a Mandibular Advancement Splint (MAS) and its positive impact on his (albeit awake) upper airway was immediate (Fig. 21b). I also sent him for another PSG study with the MAS in situ. He could now sleep on his back without choking, his sleep was a lot less fragmented, bruxing episodes were minimal during the overnight study and he awoke with less morning jaw and neck symptomology. Lavigne’s group in Montreal in 2006 had already demonstrated this in an elegant experimental controlled PSG study [1] comparing a mandibular advancement device vs conventional maxillary occlusal splint’s ability to reduce sleep bruxism. Within a few weeks Pierre was a new person. He no longer complained of recurring headache, neck pain, chronic fatigue or excessive daytime sleepiness. His physical therapist was most surprised that her manipulative therapy finally held for more than a couple of days. It was then I realized that Dentistry had a lot more to offer – it was I who was punching below my weight!

Fig. 21A The CBCT scan when the patient was biting at maximum intercsupation. His severely compromised upper airway (in black) can be clearly seen despite the fact that the patient was awake and seated upright. His worn occlusion had been Gnathologically reorganized at centric relation.

Fig. 21B CBCT scan of the same patient wearing a Mandibular Advancement Splint (set at 75% of his maximum protrusive range) for the management of his UARS. Notice the significant dimensional improvement in his pharynx especially at the retro-glossal and retro-velar regions.

Inappropriate Dentistry

Realistically, my ‘wonderful’ prosthodontic reconstruction probably worsened his airway patency and aggravated his sleep fragmentation problems. Although I meticulously restored his occlusal interface with metal crowns and provided protection and shock absorption using the stabilization splint, the sleep arousals I unknowingly facilitated must have resulted in more NREM SB! The 4 bicuspid extraction orthodontia he underwent as a teenager also couldn’t have been beneficial to his airway health.

We can no longer deny that inappropriate therapeutic retro-positioning of the mandible by well-meaning prosthodontists and orthodontists alike, as was demonstrated in Pierre’s case, could adversely influence upper airway patency and respiratory dynamics during sleep. This contentious subject has been more thoroughly discussed in our recent paper [2] on TMD patients with comorbid Upper Airway Resistance Syndrome. These TMD-UARS patients presented with distinct clinical phenotypes that we need to be aware of. Interestingly, 90.7% of this cohort reported sleep bruxism (Fig.22).

Fig. 22 Our postulate on how the TMD-UARS phenotype may have originally developed as an adaptive response to ‘awake’ disordered breathing [2]. The Southern Chinese craniofacial morphology has been previously implicated in sleep disordered breathing but uninformed dentists may further exacerbate the ‘Restricted Box’ by inappropriate treatment (e.g. retractive orthodontics with 4 bicuspid extractions and/or rigid adherence to Gnathologic dogma) of these morpho-functional adaptations (including dental malocclusion) to the patient’s pre-existing awake disordered breathing. An interdisciplinary team approach is advocated.

Could early recognition and successful intervention of the airway issues in childhood (e.g. minimally invasive ENT surgery), more appropriate interceptive orthodontics (e.g. early maxillary expansion vs bicuspid extractions) and adjunctive myofunctional therapy have prevented some of the associated craniofacial skeletal mal-development, the stomatognathic damage from sleep bruxism and improve the individual’s sleep quality at least in this patient subpopulation? The jury’s still out but evidence linking sleep bruxism, sleep disordered breathing and TMD is mounting [3]. Today, airway and sleep issues must take priority over dental dogma when planning any form of occlusal rehabilitation. Alas, orthodontists need to be reminded that every orthodontic case is a full-mouth rehabilitation!

Appropriate terminology

"The beginning of wisdom is to call things by their proper name."

Confucius

Although sleep-disordered breathing is the fashionable term banded in the medical literature to describe many conditions like OSA and UARS, to be more precise, it is upon breathing-disordered sleep and awake-disordered breathing that we as dentists can effectively exert an influence.

I believe informed dentists are uniquely positioned to play important roles in their early recognition and co-management. We must be more conscious that our very practice of dentistry can have both a positive as well as negative impact upon these maladies that have serious long-term health consequences.

Summary and Conclusions

Abnormal tooth wear and sleep bruxism may be why some patients come through our doors but we must learn to look beyond the molars!

RMMA-SB should be seen as a normal albeit complex, centrally regulated, oromotor behavior occurring during sleep and not some disorder that must be vigorously purged [4]. Likewise, awake bruxism (e.g. habitual parafunctional jaw clenching) may begin as an effective adaptive coping strategy for certain individuals competing in stoic Asian societies. Dentists, however, have a duty of care to discover and understand the individual prevailing circumstances that may have caused this RMMA transition into its maladaptive form [5].

Our identification of masseter hypertrophy (e.g. by increasing the amplitude of RMMA) as one such risk factor, puts the spotlight on Awake Bruxism thus making it a logical interventional target in the overall management of ‘destructive’ sleep bruxism and persistent myofascial TMD.

If NREM SB were indeed a physiologic compensatory mechanism to halt airway collapse, trying to eliminate the phenomenon without making an effort to find out the reasons for the airway challenge would simply be bad medicine! Patients, including children, with NREM SB should be investigated for comorbid sleep disordered breathing, in particular UARS, if they also complain of unrestorative sleep, excessive daytime sleepiness or chronic nasal congestion and demonstrate habitual mouth breathing and a forward head posture [2].

There is need for personalization of bruxism therapy through more complete characterization of each patient’s pathophysiology. The 6-week NTI trial that was presented is novel and can provide invaluable information to supplement a good history and physical examination in the identification of your patient’s unique phenotypic bruxism profile. An overnight PSG study, however, is important whenever secondary bruxism is suspected.

Patients exhibiting REM SB in particular should always be closely followed up to exclude neurologic disorders like sleep epilepsy, RDB or synucleinopathies[6,7]. In the holistic and individualized management of SB, optimal results for the patient are obtained when dentists work closely with a team of dedicated sleep professionals.

This will be my last blog on the topic of bruxism. Again, I wish to remind you that sleep bruxism and its associations with sleep disordered breathing and orofacial pain will be the focus of the upcoming Second Edmund Tay Mai Hiong Distinguished Programme scheduled 8-9 July 2018. Come join us!

David K. L. Tay, BDS, MS

References:

Landry ML, Rompre PH, de Grandmont P, Lavigne GJ., Reduction of sleep bruxism using a mandibular advancement device: An experimental controlled study. International Journal of Prosthodontics, 2006. 19: p. 549-556.

Tay DKL, Pang KP., Clinical phenotype of South-East Asian temporomandibular disorder patients with Upper Airway Resistance Syndrome. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation, 2018. 45: p. 25-33.

Balasubramaniam R, Klasser GD, Cistulli PA, Lavigne GJ., The link between Sleep Bruxism, Sleep Disordered Breathing and temporomandibular Disorders: An evidence-based review. Journal of Dental Sleep Medicine, 2014. 1(1): p. 27-37.

Raphael KG, Santiago V, Lobbezoo F., Is bruxism a disorder or a behavior? Rethinking the international consensus on defining and grading of bruxism. Journal of Oral Rehabilitation, 2016. 43: p. 791-798.

Carra, M.C., Huynh N, Fleury B, Lavigne GJ., Overview on sleep bruxism for sleep medicine clinicians. Sleep medicine clinics, 2015. 10(3): p. 375-384.

Abe S, Gagnon J-F, Montplaisir J Y, Postuma RB, Rompre P, Huynh NT, Kato T, Kawano F, Lavigne GJ. Sleep bruxism and oromandibular myoclonus in rapid eye movement sleep behavior disorder: a preliminary report. Sleep Med, 2013. 10: p.1024-30.

Postuma RB, Gagnon J-F, Betrand J-A, Marchand DG, Montplaisir JY. Parkinson risk in idiopathic REM sleep behavior disorder. Preparing for neuroprotective trials. Neurology 2015. 84: p.1104-1113.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author's alone.

![Fig. 22 Our postulate on how the TMD-UARS phenotype may have originally developed as an adaptive response to ‘awake’ disordered breathing [2]. The Southern Chinese craniofacial morphology has been previously implicated in sleep disordered breathing …](https://images.squarespace-cdn.com/content/v1/579eebd42e69cf81541e8395/1528465439356-166B97AL41D0RVYCAUJX/Fig22.png)